Drug Prices

Costs and Outrage Rise in the U.S.

By Robert Langreth

Updated Nov 9, 2016 2:00 PM UTC - Bloomberg

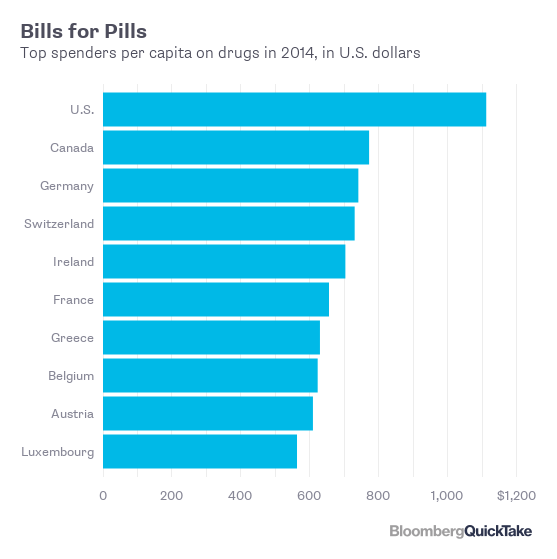

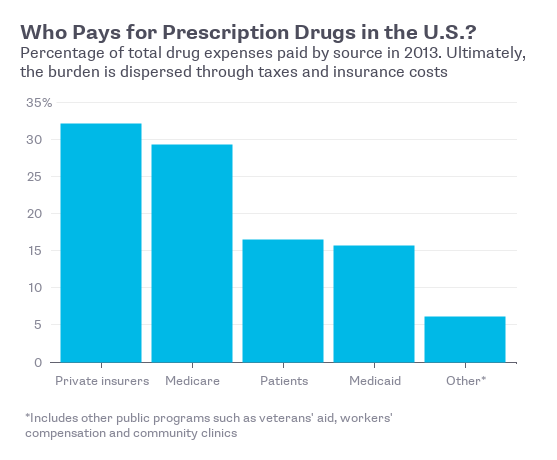

Americans spend more on prescription drugs — average costs are about $1,100 per person per year — than anyone else in the world. Itfs true that they take a lot of pills. But what really sets the U.S. apart from most other countries is high prices. Cancer drugs in the U.S. routinely cost $10,000 a month. Even prices for old drugs are spiking, as companies buy up medicines that face no competition and boost charges. While private insurers and government programs pick up the biggest share of the bill, high drug costs are ultimately passed down to the public through premiums and taxes. More than three-quarters of Americans in one poll said that the federal government should make drug affordability its first health-care priority.

The Situation

Drug companies increasingly have become the subject of outrage and scrutiny in the U.S. Lawmakers have probed how they set prices, and the Justice Department is investigating possible price collusion by more than a dozen companies that make generic drugs. Some politicians, notably Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in her unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. presidency, have accused drugmakers of price gouging. Martin Shkreli became a symbol of greed in 2015 when the company he then headed, Turing Pharmaceuticals, bought rights to an old anti-parasitic drug and raised its price more than 50-fold to $750 a pill. Turing later offered hospitals discounts on the drug of up to 50 percent. Prescription drug spending in the U.S. began to surge in 2014 after six years of increases held down by the spread of generic drug use. It rose 8.5 percent in 2015. Specialty drugs (high-cost treatments, mostly for complex conditions) account for much of the spending growth. The current backlash first erupted in 2013 when Gilead Sciences released the groundbreaking hepatitis cure Sovaldi at $84,000 for a 12-week course. The steep price and stampede of patients to get the drug led many insurers to restrict coverage to the sickest patients.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

The Background

Unlike other nations, the U.S. doesnft directly regulate medicine prices. In Europe, the second-largest pharmaceutical market after the U.S., governments negotiate directly with drugmakers to limit what their state-funded health systems pay. The U.K.fs National Health Service has refused to pay for some cancer drugs widely used in the U.S. on the grounds that they donft constitute value for money. In the U.S., drug companies can more or less set whatever price the market will bear. For most outpatient drugs reimbursed through Medicaid, the public health program for the poor, drugmakers must provide the government rebates. But most medicine costs are paid for by Medicare, the government program for the elderly, or by private insurers. When prescription-drug benefits were added to Medicare under a 2003 law, the pharmaceutical industry successfully lobbied to prohibit the federal government from using its huge purchasing power to negotiate drug prices. Private payers typically rely on third-party pharmacy-benefit managers, such as Express Scripts, to negotiate discounts. Often they make exclusive deals with drugmakers, which limits the choice of drugs patients have. Patients directly pay about 17 percent of prescription medicine costs out of their own pockets. In a 2013 survey, one in five adults in the U.S. said they failed to complete a prescribed course of medicine because of cost. The figure was one in ten in Germany, Canada and Australia.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The Argument

Pharmaceutical companies argue that they need robust profits to bankroll the development of future medical advances and that restricting prices would harm innovation. They highlight the benefits of medicines such as Sovaldi, which has a cure rate superior to treatments that cost nearly as much. Critics point to the industryfs fat profit margins and say companies exaggerate drug-development costs. Doctors and insurance executives worry that many medicines are rapidly becoming unaffordable. Clinton has proposed that the federal government determine how much long-available drugs should cost and use mechanisms such as fines or mandatory rebates to punish companies that raise prices on them excessively. Advocates of greater price regulation argue that it neednft hamper innovation. They say drugmakers could reduce spending on marketing and cite an analysis that found promotional budgets exceed those for research and development at most big companies.

The Reference Shelf

- A Bloomberg news analysis of drug pricing practices.

- A Center for American Progress report advances proposals for addressing high drug prices.

- An article in the Harvard Business Review argues that U.S. consumers are footing the global bill for developing new drugs.

- A Congressional Research Service report examines policy concerns around specialty drug prices.

- An IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics report reviews drug spending shifts in the U.S.

- Pharmaceutical companies defend drug costs on an industry website.